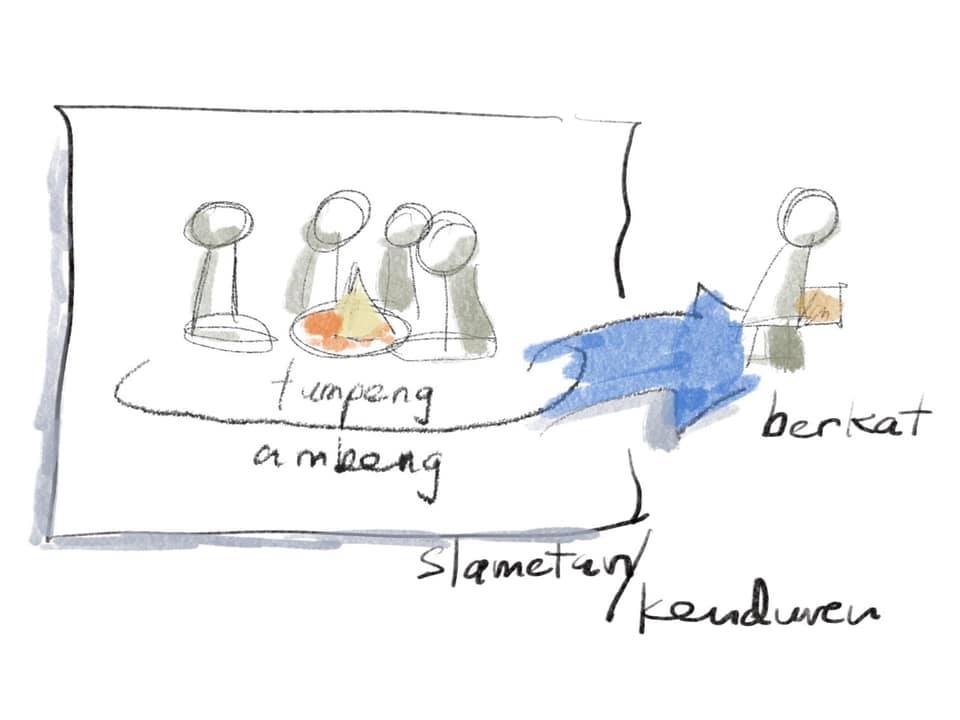

In a slametan or kenduri, the men are mostly involved in the main area where prayers are recited.

Where are the womenfolk?

Mostly, at the back, preparing the communal feast known as nasi ambeng.

The preparation of the dishes take time and for those who are familiar with the process, it is done in a certain sequence.

The amount of work needed to prepare the various dishes could only reflect one thing – communal cooking. The preparation was not meant to be done by one family. It takes a team in the kitchen to ensure that all the dishes are done right.

Some dishes cannot be rushed and make take very long hours, resulting possibly in shift work.

The meal is also not consumed alone and at the ritual itself.

It is meant to be divided among the congregants, and packed to be brought home to share with the family of the men who attended. Hence the need to ensure proper preparation so that the food do not turn bad too soon.

Only a small amount was being eaten while the rest are packed for home.

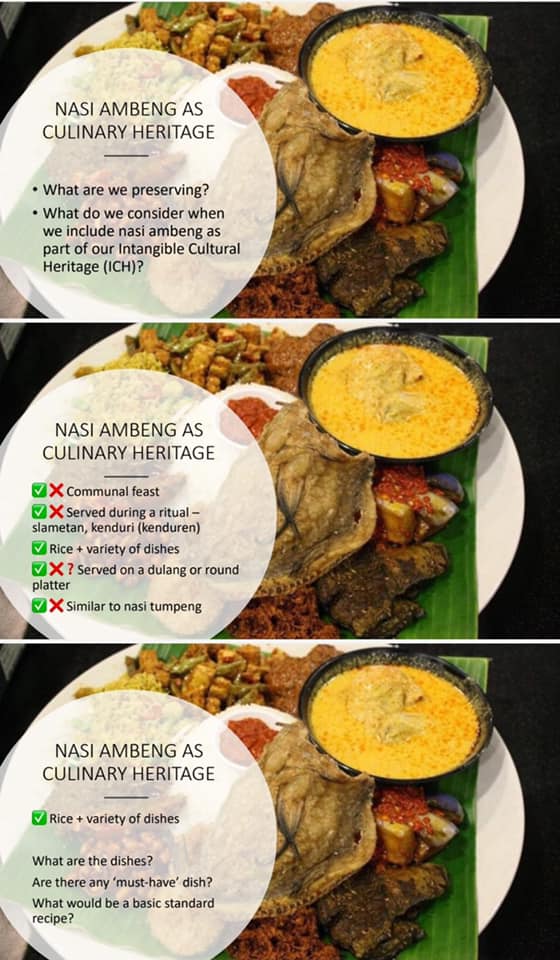

Due to this practical feature as well as a need to move away from pre-Islamic symbolism; that we see a difference between the arrangements for nasi ambeng and nasi tumpeng.

In nasi tumpeng, the conical or mount of rice is surrounded by the dishes to represent that flora and fauna of a mountain in the centre.

In most nasi ambeng, the dishes are placed in the centre on top of the rice usually separated with a layer of banana leaf, where it is easier to reach the rice as its not in the centre.

The rice is divided followed by the dishes.

However, it seems that both of them appear to be similar.

The displacement of the nasi ambeng away from it’s ritual and communal setting makes it a challenge for serving in a commercial setting.

For one, conceptually, there should not be a nasi ambeng for one or two persons.

Secondly, it takes much resources to cook all the dishes for small orders.

Nevertheless, cultural traditions and practices evolve.

In a more religious setting, it could be considered as cultural innovation or cultural bida’ah.

The emphasis on consuming nasi ambeng at the same sitting is also likely to encourage excessive eating but it was not meant to be so.

In the traditions of nasi tumpeng, the various flavours of the dishes were meant to reflect the flavours of life.

As the innovated tradition of the nasi ambeng is likely to follow suit, we should expect the same practice of consumption but we see the picking of dishes and the neglect of those that we do not favour.

What began as an element of communal gatherings has now become something less that communal.

That’s the life of any cultural artefact- it evolves and changes.

We decide how we want to preserve and sustain it’s initial and early intention.